“When Strangers Meet”: John Bowlby and Harry Harlow on Attachment Behavior

Frank C. P. van der Horst1 , Helen A. LeRoy2 and René van der Veer1

(1) Centre for Child and Family Studies, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9555, NL-2300RB Leiden, The Netherlands

(2) Harlow Primate Laboratory, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA

Frank C. P. van der Horst

Email: fhorst@fsw.leidenuniv.nl

Received: 12 February 2008 Accepted: 21 August 2008 Published online: 3 September 2008

Abstract From 1957 through the mid-1970s, John Bowlby, one of the founders of attachment theory, was in close personal and scientific contact with Harry Harlow. In constructing his new theory on the nature of the bond between children and their caregivers, Bowlby profited highly from Harlow’s experimental work with rhesus monkeys. Harlow in his turn was influenced and inspired by Bowlby’s new thinking. On the basis of the correspondence between Harlow and Bowlby, their mutual participation in scientific meetings, archival materials, and an analysis of their scholarly writings, both the personal relationship between John Bowlby and Harry Harlow and the cross-fertilization of their work are described.

Keywords Attachment theory - Animal psychology - Ethology - Animal behavior - Infant–mother relations - History Frank C.P. van der Horst is a PhD student and Lecturer at the Centre for Child and Family Studies at Leiden University, The Netherlands. The work presented in this special issue is part of his doctoral thesis on the roots of Bowlby’s attachment theory. The defence of this thesis, titled John Bowlby and ethology: a study of cross-fertilization, is scheduled for early 2009.

Frank C.P. van der Horst is a PhD student and Lecturer at the Centre for Child and Family Studies at Leiden University, The Netherlands. The work presented in this special issue is part of his doctoral thesis on the roots of Bowlby’s attachment theory. The defence of this thesis, titled John Bowlby and ethology: a study of cross-fertilization, is scheduled for early 2009.

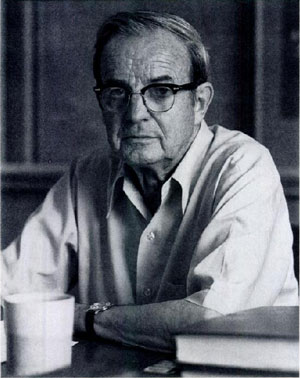

Helen A. LeRoy recently retired from the Harlow Primate Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison after working there for nearly half a century. During that time, she worked closely with Harry Harlow from her arrival in 1958 until his retirement in 1974. She was Harlow’s executive assistant and was his help and stay in the editing of the Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology.

René van der Veer is Professor of History of Educational Thinking at Leiden University, The Netherlands. His research addresses the work of key educational thinkers such as Gal’perin, Janet, Piaget, Vygotsky, Werner, and Wallon. In a longer study the origin of the idea of the social mind was traced. He is on the Editorial Board of Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Sciences.

Introduction

Today, one can pick up almost any introductory, general, or developmental psychology textbook (e.g., DeHart et al. 2004; Cole and Cole 2005) and find references to British child psychiatrist John Bowlby (1907–1990) and American animal psychologist Harry Harlow (1905–1981). Quite often their work is discussed in tandem. Bowlby was a clinician by training and Harlow an experimentalist. Despite these rather different backgrounds, the two men had several things in common. One of them was that they showed no hesitation in expressing views that went against the prevailing Zeitgeist. In the 1950s and 1960s, both Bowlby and Harlow formulated new ideas on the nature of the bond between child and caregiver. They defied the prevailing psychoanalytic and learning theoretical views that dominated psychological thinking from the 1930s. Although it has been argued (Singer 1975) that Harlow’s experimenting had no influence on Bowlby’s theorizing, here it will become clear that Bowlby used Harlow’s surrogate work with rhesus monkeys as much needed empirical support for his emerging theory of attachment in which he explained the nature and function of the affectional bonds between children and their caregivers (Bowlby 1958, 1969/1982). In his turn, Harlow was influenced by Bowlby’s thinking and tried to model his rhesus work to support Bowlby’s new theoretical framework (e.g., Seay et al. 1962; Seay and Harlow 1965).

The theories of Harlow and Bowlby are well-known but so far little was known about the personal and professional relationships between these two giants in the field. In this contribution, on the basis of the correspondence between Harlow and Bowlby1, their joint participation in scientific meetings, archival materials, and an analysis of their scholarly writings, an attempt is made to delineate the cross-fertilization of their work during the most active years of their acquaintance from 1957 through the mid-1970s. It will be demonstrated that Bowlby and Harlow’s interests converged as Harlow shifted his focus to a developmental approach shortly before the two met. Their introduction at a distance by British ethologist Robert Hinde was the beginning of an exchange of ideas that resulted in groundbreaking experimenting and theorizing that affects the field of developmental psychology to this day.

Bowlby’s Early Career (1938–1957): from Kleinian Psychoanalysis to Real Life

John Bowlby, who received a Master’s degree from Cambridge University and an M.D. from University College Hospital in London, was trained in psychoanalysis. He practiced as a clinician and joined the staff of the Tavistock Clinic in London in 1946, where he spent the remainder of his professional career (cf. Van Dijken 1998; Van Dijken et al. 1998). There is no doubt that he will be remembered in history as “the father of attachment theory”. Bowlby’s career evolved on the basis of a single theme, the relationship between mother and infant, and the effects of the pattern established early on upon the developmental outcome of the offspring. He mounted a scientific challenge to dominant psychoanalytical views in British psychiatry, such as those held by Anna Freud and Melanie Klein (Berrios and Freeman 1991).

In an interview with Robert Karen (1994, pp. 45–46), Bowlby described an influential experience in 1938, while training under the supervision of psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. Contrary to Klein, who believed all behavior was motivated by inner feelings, Bowlby felt that external relationships, e.g., the way a parent treated a child, were important to consider in understanding the child’s behavior. At the time, he was seeing an anxious, hyperactive child as a patient five days a week. The boy’s mother would sit in the waiting room, and Bowlby noticed that she too seemed quite anxious and unhappy. When he told Klein he wanted to talk to the mother as well, Klein refused adamantly, dismissing the mother as a possible causal or related factor in the child’s behavior. Bowlby was thoroughly annoyed and gradually distanced himself from the Melanie Klein school of thought. Later, in 1948, through the work of Tavistock social worker James Robertson, with whom he would work closely over the years, Bowlby became interested in recording the responses shown by children between the ages of 12 months and 4 years upon separation from their mothers or attachment figures (Bowlby 1960a).

In 1950, as part of a World Health Organization (WHO) project, Bowlby (1951) undertook a literature survey in order to test the hypothesis that “separation experiences are pathogenic” (Bowlby 1958). Homeless children had become a major problem after World War II, and in his WHO report, Bowlby warned that children deprived of their mothers were at risk for physical and mental illness. After surveying the literature, Bowlby et al. (1952, p. 82) concluded:

It became clear that this hypothesis is well supported by evidence and the team is now planning to concentrate on understanding the psychological processes which lead to the grave personality disturbances—severe anxiety conditions and psychopathic personality—which we now know sometimes follow experiences of separation.

We may conclude, then, that Bowlby was convinced at the time that (repeated) separation experiences may seriously harm the mental health of children and that the existing literature (e.g. on hospitalization) proved his point of view. He valued empirical studies and emphasized the importance of objective observation of real-life experiences. However, he still lacked the theoretical apparatus to understand the causal mechanisms behind the phenomena he observed. Also, he knew of no experiments that manipulated the potentially relevant variables in the domain of attachment formation. It was in this situation that he chanced upon the emerging science of ethology and the experimental work of Harlow.

In the subsequent years Bowlby made increasing use of ethological findings and theorizing guided by British ethologist, colleague and life-long friend Robert Hinde (Van der Horst et al. 2007). Bowlby (1957, 1960c) acknowledged a deep and pervasive interest in ethology beginning about 1951, which was sparked by Konrad Lorenz’s (1935, 1937) gosling work. His talk to the members of the British Psycho-Analytical Society on June 19, 1957 (published as Bowlby 1958) testifies of his growing confidence in the relevance of ethology.

Harlow’s Early Career (1930–1957): from Conditioning Rats to Studying Monkey Love

Harry Harlow received a Ph.D. in psychology from Stanford University in 1930 and spent the remainder of his academic career as a professor at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Harlow was educated in the psychological tradition of the 1920s and 1930s, a time when psychology was making an effort to become a ‘real’ science. Studying behavior was a case of controlling the environment and varying one particular condition. It was a time when behaviorist views carried the day and the conditioned responses of Norwegian rats were the key to understanding mental life. So, when Harlow was appointed at Wisconsin in 1930 and found that the psychology department’s chairman had the rat laboratory dismantled and it was not about to be replaced, he was greatly inconvenienced (Harlow 1977, p. 138–139; Suomi and LeRoy 1982).

It was only at the suggestion of the chairman’s wife that Harlow decided to study primates at the local zoo and he soon found out that the intellectual capabilities of the monkeys were far greater than those of rats (Suomi and LeRoy 1982). To study these capabilities more rigorously and effectively Harlow developed the Wisconsin General Test Apparatus (WGTA; Harlow and Bromer 1938) by which it was possible to present the monkeys with a large number of learning tests in a highly standardized way. With it he tested the monkeys with discrimination learning and memory tasks (e.g., Harlow 1943, 1944). Harlow’s next step was to study cortical localization of learning capabilities by doing lesion studies with monkeys (e.g., Harlow and Dagnon 1943; Harlow and Settlage 1947; Moss and Harlow 1948). By lesioning different areas of the brain, Harlow noted that each of the operated monkeys performed differently on the WGTA tests. This work was basically similar to the work done by Lashley (e.g., Lashley 1950).

In the late 1940s, Harlow achieved “a major conceptual and methodological breakthrough” (Suomi and LeRoy 1982, p. 321) by identifying the formation of learning sets in monkeys (Harlow 1949). Harlow demonstrated that his monkeys “learned to learn” and that they acquired a strategy for problem-solving. As methods of studying processes underlying monkey learning were exhausted, Harlow in the early 1950s turned to studying motivation and the ontogeny of learning. This type of developmental research required the establishment of a breeding colony of rhesus monkeys. It was at this point that Harlow’s attention was drawn to the phenomenon of affection.

Harlow had always had problems importing monkeys: apart from being very expensive, they were often ill upon arrival and infected the other monkeys in the laboratory. In 1956, following procedures of Van Wagenen (1950), he decided to raise his own rhesus monkeys, and thus the Wisconsin lab became the first self-sustaining colony of monkeys in the US. The monkeys were kept separated at all times to avoid any spread of disease. The results of this procedure were remarkable for those who could see it: the monkeys Harlow raised were physically perfectly healthy, but their social behavior was very awkward. They were simply unable to socially interact with each other. Another striking observation Harlow made was that the infant monkeys “clung to [the diapers on the floor of their cage] and engaged in violent temper tantrums when the pads were removed and replaced for sanitary reasons” (Harlow 1958, p. 675). Harlow wondered whether these observations could mean anything for the needs of human children.

Just two months prior to Bowlby’s British Psycho-Analytical Society address which discussed in great depth the child’s tie to the mother, Harlow spoke on April 20, 1957 at a conference in Washington, D.C. The title of his address was the “Experimental Analysis of Behavior” and it included a discussion of trends in this area. Harlow began his address by stating that “no behavior is too complicated to analyze experimentally, if only the proper techniques can be discovered and developed” (Harlow 1957, p. 485). He went on to emphasize the importance of a developing trend toward longitudinal studies (psychology had traditionally been concerned with a cross-sectional approach), and he told how:

I have followed with interest the changes in my own research programs and the development of these programs. The experimental S that has consumed almost all my research time has been the rhesus monkey. When I initially approached the experimental analysis of this animal’s behavior, I approached it in the classical, cross-sectional manner (...). If it had not been for the fact that my monkey Ss continued to live after they had solved a problem and that they were not expendable in view of the available financial support, I might still be engaged in cross-sectional studies of the monkey’s behavior. (Harlow 1957, p. 487)

These comments clearly indicate that Harlow was moving towards experimental developmental research, the type of research that Bowlby so badly needed at the time. Harlow was now on the threshold of the affectional studies, for which he would become famous. He explained that:

More recently we have planned and initiated much more extensive longitudinal studies in which we have separated infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers at birth and raised them under the controlled conditions of the laboratory. We have been successful in raising over fifty of these young animals, and we have obtained data on their learning development from birth through three years of age. (...) We have found the longitudinal approach to the experimental analysis of behavior interesting and even exciting, and we are now extending this type of analysis to other areas than learning, perception, and motivation. (...) [W]e are planning and conducting systematic longitudinal studies on the development of emotional responses. (Harlow 1957, p. 488)

Just like Bowlby before his fellow psychiatrists of the British Psycho-Analytical society, Harlow (1957, p. 490), before an audience of clinical psychologists, stressed the importance of observational methods in this process, something that was of course very obvious to him.

At the present time (...) we are interested in tracing the development of various patterns of emotional behavior. (...) We began by looking for response patterns which might fit. (...) But this observational study (...) is gradually taking on the characteristics of an experiment. As we gain sophistication about the monkey’s emotional responses, we become more selective in the patterns which we observe.

It was because of their mutual interest in this area of emotional behavior and responses that Harlow and Bowlby became acquainted. In Harlow’s words: “It is an understatement to add that we have research interests in common” (Harlow in a letter to Bowlby, January 27, 1958).

Ethology and Animal Psychology: Contrasting Approaches to Animal Behavior

It was not self-evident for a British ethologically oriented psychiatrist and an American animal behaviorist to meet in those days. In the 1950s, there was a great barrier between ethologists (who were mostly biologists by training) and students of animal behavior (mostly psychologists). Ethologists emphasized observation of animals in their natural habitat, whereas comparative psychologists relied on rigorous experimentation in the laboratory. The culmination of this debate was a 1953 critique by Theodore Schneirla’s student Daniel Lehrman of Lorenz’s concept of instinct, at that time the central theoretical construct of ethology (Lehrman 1953). But in contrast to what might be expected, when Lehrman visited Europe in 1954 and met with leading ethologists, he was very well received. Just like many of the ethologists, Lehrman had a background in evolutionary biology and ornithology and this may have been essential in bridging their differences. Although Lorenz never acknowledged Lehrman’s ideas, they later became mainstream ethology (Griffiths 2004). Eventually Hinde (1966) wrote his authoritative book Animal behaviour which was essentially “a synthesis of ethology and comparative psychology” (cf. Van der Horst et al. 2007, p. 9–10).

In this climate of contrasting views, Hinde and Harlow met for the first time in Palo Alto in early 1957 at a conference organized by Frank Beach that was intended to bring together a group of European ethologists (Niko Tinbergen, Gerard Baerends, Jan van Iersel, David Vowles, Eckhardt Hess and Robert Hinde) with a group of mainly North-American comparative and experimental psychologists (Frank Beach, Donald Hebb, Daniel Lehrman, Jay Rosenblatt, Karl Lashley and Harry Harlow). Hinde has good memories of the event: “It was a wonderful conference, about three weeks, [where you had] nothing to publish, and if you did not finish what you had to say today there was always tomorrow” (Robert Hinde, personal communication, March 14, 2007). After their first encounter, Hinde and Harlow met several times in the late fifties and sixties. Although they influenced each other and their relationship was very cordial in the days they interacted, Hinde in retrospect remembers that at that time their approaches were still rather far apart:

I must have next met Harry when I visited Madison and was appalled by this room full of cages with babies going “whoowhoowhoo” and Harlow had no sensitivity at that point that he was damaging these infants. At that time I was beginning to work on mother–infant relations in monkeys myself, but I already knew enough about monkeys to know that that “whoo”-call was a distress call. These experiments had their restrictions, but they did show certain important things. After that I saw him at least once a year for a while as he asked me to join his scientific committee. Of course his results influenced my way of thinking, but I was then an ethologist and not keen on his laboratory orientation. And I could never have attempted to do the sort of research that he did because our colony only had six adult males and two or three females in each group. We attempted to create an approximation to a normal social situation: it was a long way off, of course, but at least it was social. (Robert Hinde, personal communication, August 22 and 26, 2005; March 14, 2007)

Despite these differences in theoretical orientation, it was Robert Hinde who would eventually establish contact between Bowlby and Harlow. At the Palo Alto conference, Hinde and Harlow had a discussion on motherhood and after returning home Hinde informed Bowlby that Harlow was interested in Bowlby’s recent work on this subject (Stephen Suomi, personal communication, September 27, 2006; Karen 1994; Hrdy 1999; Blum 2002; Van der Horst et al. 2007).

Harlow and Bowlby Become Acquainted in 1957

It was just several months later that Bowlby and Harlow introduced themselves by letter. The written record of their relationship commenced with a letter dated August 8, 1957 in which Bowlby expressed his interest:

Robert Hinde tells me that you were interested in my recent paper when he showed it to you at Palo Alto and at his suggestion I am now sending you a copy. I need hardly say I would be most grateful for any comments and criticisms you cared to make. I shall be at the Center at Palo Alto from mid-September and will be preparing it for publication then. Robert Hinde told me of your experimental work on maternal responses in monkeys. If you have any papers or typescripts I would be very grateful for them. If there were a chance, I would try to visit you next Spring when I hope to be moving around U.S.A. (Bowlby in a letter to Harlow, August 8, 1957)

The paper which Bowlby sent to Harlow at the time was a draft of “The nature of the child’s tie to his mother” (Bowlby 1958). Harlow replied by return of post, thanking Bowlby for the paper, which he several years later (in a letter to Bowlby, March 25, 1959) would refer to as a “reference bible”:

[Y]our interests are (...) closely akin to a research program I am developing on maternal responses in monkeys. I certainly hope that you can pay a visit to my laboratory sometime during this forthcoming year. At the moment our researches are just getting underway, and I hope to use these materials for my American Psychological Association Presidential Address in September, 1958. This address will be the first formal presentation of these researches. (Harlow in a letter to Bowlby, August 16, 1957)

Mutual Referencing After 1957

It was only after the two men began corresponding in August, 1957, that they began referring to each other’s writings. A review of Bowlby’s publications from 1951–1957 (Bowlby 1951, 1953, 1957; Bowlby et al. 1952, 1956; Robertson and Bowlby 1953) yields no mention of Harlow’s work. Likewise, we find no reference to Bowlby’s work in Harlow’s first developmental writings (Harlow 1957).

The early correspondence resulted in the planning of mutual visits and in the exchange of reprints.2 Seven of Bowlby’s publications (Bowlby et al. 1952, 1956; Bowlby 1958, 1960a, b, c, 1961c) have been found in Harlow’s reprint collection, in addition to two volumes on Attachment and Loss (Bowlby 1969/1982, 1973). It is especially interesting to see Harlow’s notes jotted in the margins of Bowlby’s papers.

As a result of the interchange, the first reference to Harlow’s work appears in Bowlby’s work (Bowlby 1958). This paper was an expanded version of an address Bowlby gave before the British Psycho-Analytical Society on June 19, 1957. The paper is concerned with conceptualizing the nature of the young child’s tie to his mother, the dynamics which promote and underlie this tie. Bowlby described four alternative views found in the psychoanalytic or psychological literature at the time. He then went on to present his own theoretical perspective. He emphasized that his view was based on direct observation of infants and young children, rather than on retrospective analysis of older subjects as was the typical base for psychoanalytic theorizing at the time. Bowlby (1958, p. 351) went on to state:

The longer I contemplated the diverse clinical evidence the more dissatisfied I became with the views current in psychoanalytical and psychological literature and the more I found myself turning to the ethologists for help. The extent to which I have drawn on concepts of ethology will be apparent.

The four then contemporary views he described were first of all the cupboard-love theory of object relations, according to which the physiological needs for food and warmth are met by the mother, through which the baby gradually learns to regard the mother as the source of all gratification and love. Secondly, primary object sucking, which states that the infant has a built-in need to orally attach to a breast and subsequently learns the breast is attached to the mother and then relates to her also. Thirdly, primary object clinging, according to which the infant has a built-in need to touch and cling to a human being, independent of food, but just as important. And finally, primary return-to-womb craving, which holds that the infant resents its removal from the womb at birth and wants to return there.

Bowlby then described his own hypothesis, one of much greater complexity and quite controversial at the time (Karen 1994; Hrdy 1999), as “Component Instinctual Responses”. He believed that five responses comprise attachment behavior—sucking, clinging, following, crying, and smiling—also acknowledging that many more may exist. He explained that his theory was “rooted firmly in biological theory and requires no dynamic which is not plainly explicable in terms of the survival of the species” (Bowlby 1958, p. 369).

A main point of Bowlby’s argument was that no one response was more primary than another. He believed it was a mistake to emphasize sucking and feeding as the most important. Pointing out the inadequacy of human infant studies to date in terms of illustrating his hypothesis, Bowlby turned to observation of animals. It was in this context that Bowlby first cited Harlow’s research. He clearly used Harlow’s findings to undermine the psychoanalytic idea that all attachment develops through oral gratification. Harlow had specifically investigated the importance of clinging. Bowlby cited Harlow’s yet unpublished nonhuman primate data “on the attachment behaviour of young rhesus monkeys” (later published as Harlow 1958):

Clinging appears to be a universal characteristic of primate infants and is found from the lemurs up to anthropoid apes and human babies... Though in the higher species mothers play a role in holding their infants, those of lower species do little for them; in all it is plain that in the wild the infant’s life depends, indeed literally hangs, on the efficiency of his clinging response... In at least two different species (...) there is first-hand evidence that clinging occurs before sucking... We may conclude, therefore, that in sub-human primates clinging is a primary response, first exhibited independently of food. Harlow (...) removed [young rhesus monkeys] from their mothers at birth, they are provided with the choice of two varieties of model to which to cling and from which to take food... Preliminary results strongly suggest that the preferred model is the one which is more ‘comf[ortable]’ to cling to rather than the one which provides food. (Bowlby 1958, p. 366)

Harlow and Bowlby Finally Meet in 1958

After the first two letters in August, 1957, eight additional letters were exchanged during the period Bowlby spent at the Palo Alto Center from mid-September, 1957 through mid-June, 1958. In these letters, the two men discussed their mutual interests and made arrangements for Bowlby to visit Harlow’s lab in Madison as Bowlby was finally able to carry out the plans of a visit he had mentioned in his first letter. Bowlby attended one of Harlow’s lectures on April 26, 1958 and visited his laboratory for two days in June of that same year (Zazzo 1979). In a letter to his wife Bowlby shows his enthusiasm after their first encounter:

You may remember I went to hear the final paper of the [Monterey] conference—an address by Harry Harlow of Wisconsin on mother infant interaction in monkeys. His stuff is a tremendous confirmation of the Child’s Tie paper, which he quoted. Afterwards Chris[toph Heinicke] heard him remark, in very good humour, to a friend: “You know, I thought I had got hold of a really original idea [and] then to find that bastard Bowlby had beaten me to it!” This is not really true [and] I think we can say it’s a dead heat—[and] the work of each supports the other. We had a very aimable chat [and] arranged to meet in June. (Bowlby in a letter to Ursula, April 28, 1958; AMWL: PP/BOW/B.1/20)3

The lecture Bowlby attended was a presentation Harlow gave at the meetings of the American Philosophical Society (published as Harlow and Zimmermann 1958) on the development of affectional responses in infant monkeys. There Harlow touched upon, in contrast with Bowlby’s earlier in-depth analysis of the same matter, the various psychoanalytic theoretical positions concerning the bond of the infant to the mother. Referring to their personal contacts, Harlow (Harlow and Zimmermann 1958, p. 501) mentioned that “Bowlby has given approximately equal emphasis to primary clinging (contact) and sucking as innate affectional components, and at a later maturational level, visual and auditory following”. This was Bowlby’s first appearance in a Harlow publication.

Bowlby visited Madison in June, 1958 and wrote to Harlow on the 26th, thanking him for his hospitality, and adding: “I shall look forward to keeping in touch (...). I hope too you will put me on your list to send mimeograph versions as and when your stuff goes further forward. We will reciprocate.” By June of 1958, the earlier formal salutations and closings “Dear Professor Harlow” and “Yours sincerely” or “Dear Dr. Bowlby” and “Cordially” had changed to a much more informal tone, becoming “Dear Harry” and “Yours ever, John”, or “Dear John” and “Best personal wishes, Harry”.

Two months later, on August 31, 1958, Harlow delivered his famous presidential address on “The nature of love” to the American Psychological Association. “The recent writings of John Bowlby” are mentioned in the published paper (Harlow 1958, p. 673), to the effect that he recognized the mother’s importance in providing the infant with intimate physical contact, as well as serving as a source of nutrition. Harlow also positively mentioned Bowlby’s notion of ‘primary object following’, i.e. the tendency to visually and orally search the mother. The fact that Bowlby is mentioned twice in the presidential address is of some significance given that Harlow mentions but six names of researchers and hardly discusses their ideas.

Ethology Further Emphasized in Bowlby’s Work

It was in July, 1959, that Bowlby (1960c) read a paper on ethology before the Congress of the International Psycho-Analytical Association in Copenhagen. Bowlby began his paper by remarking that eight years had now passed since his interest in ethology had been aroused, initially by Lorenz’s gosling work.

From this time forward the further I read and the more ethologists I met the more I felt a kinship with them. Here were first-rate scientists studying the family life of lower species who were not only making observations that were at least analogous to those made of human family life but whose interests, like those of analysts, lay in the field of instinctive behaviour, conflict, and the many surprising and sometimes pathological outcomes of conflict... A main reason I value ethology is that it gives us a wide range of new concepts to try out in our theorizing. (Bowlby 1960c, p. 313)

At the same time, Bowlby was cautious about extrapolating or generalizing from one species to another. He shared this restraint with Harlow who often reiterated that “monkeys are not furry little men with tails.” Both, however, were convinced of the importance of animal research in providing a better understanding of human social behavior. Bowlby (1960c, p. 314) expressed his view thus:

Man is a species in his own right with certain unusual characteristics. It may be therefore that none of the ideas stemming from studies of lower species is relevant. Yet this seems improbable. (...) [W]e share anatomical and physiological features with lower species, and it would be odd were we to share none of the behavioural features which go with them.

Carrying the notion further, Bowlby explained his efforts to use ideas gleaned from ethology in order to understand the ontogeny of what psychoanalysts called ‘object relations’. For a specific example of instinctual response systems present in the young, which facilitate the attachment of the infant to a mother figure without the mother’s active participation, Bowlby (1960c, p. 314) referred to and cited Harlow’s surrogate mother research: “a newborn monkey will cling to a dummy provided it is soft and comfortable. The provision of food and warmth are quite unnecessary. These young creatures follow for the sake of following and cling for the sake of clinging.”

Several pages later, in discussing the consequences of disrupting the mother–infant bond, Bowlby mentioned the substitution of one behavior for another due to frustration when the normal event was blocked, e.g., thumb sucking or overeating when denied maternal access. He drew a parallel with nonnutritive sucking in chimpanzees and rhesus monkeys:

In Harlow’s laboratory I have seen a full-grown rhesus female who habitually sucked her own breast and a male who sucked his penis. Both had been reared in isolation. In these cases what we should all describe as oral symptoms had developed as a result of depriving the infant of a relationship with a mother-figure... May it not be the same for oral symptoms in human infants? (Bowlby 1960c, p. 316)

In his conclusions, Bowlby once again stated that an understanding of biological processes is required in order to understand the psychological concomitants of biological processes. Two months later, in September, 1959, the first symposium organized by Bowlby was held at the Tavistock Clinic and Harlow was an invited participant.

Mutual Contacts: the Ciba-symposia from 1959 to 1965

The initial introduction by Hinde and Bowlby’s visit to Harlow’s laboratory led to a fruitful cooperation during the following years. Just prior to a Chicago meeting, Harlow invited Bowlby to visit the University of Wisconsin again, but Bowlby replied with regrets on March 30, 1961, stating that he was already booked up with engagements relative to a forthcoming Chicago trip and would hope to visit Harlow’s lab in 1962 or 1963 during a “more leisurely trip in the States. Looking forward to seeing you in the Autumn” (Bowlby in a letter to Harlow, March 30, 1961). Bowlby was undoubtedly referring to the second of four so-called Ciba-symposia4 to be held in London in the fall of 1961.

The Ciba-symposia followed the design for interdisciplinary discussion Bowlby had first experienced during the meetings of the WHO on the psychobiological development of the child, which he attended in the early 1950s (Tanner and Inhelder 1971; cf. Foss 1969). Bowlby was impressed by the series’ innovative format: the meetings brought together a small group of researchers from different countries and disciplines for the purpose of promoting the knowledge of the subject matter and enhancing a mutual understanding of each other’s work and views.

Thus, following this model, Bowlby convened and chaired the Tavistock study group on mother–infant interaction, a series of four meetings at two-year intervals, held in the house of the Ciba foundation in London between 1959 and 1965. Harlow was a major participant of and contributor to the Ciba-symposia in 1959 (Harlow 1961), 1961 (Harlow 1963), and 1965 (Harlow and Harlow 1969), but was unable to attend the third session in 1963. In his introduction to the proceedings of the last meeting, Bowlby contended that his early hopes had come true:

As the series of meetings proceeds, reserves and misconceptions, inevitable when strangers from strange disciplines first meet, will recede and give place to an increasing grasp of what the other is attempting and why; to cross-fertilization of related fields; to mutual understanding and personal friendship. (Bowlby in Foss 1969, p. xiii)

It is clear that both Harlow and Bowlby shared these positive feelings about the effectiveness of the symposia and that Bowlby was very pleased with the way things worked out. During the second study group, on September 7 and 9, 1961, Bowlby wrote to his wife Ursula:

There is widespread enthusiasm at the way the study group is going, regrets we have so little time, [and] shows demand we meet again in [two] years time—(after our holiday next time). The atmosphere is much less tense this time—Jack Gewirtz no longer a problem child—[and] communication is quick, spontaneous [and] effective. The two year gap, I’m sure, is better than one year. It has given plenty of time for everyone to digest the lessons of the first meeting, [and] there has been much private visiting [and] private communication between the members since. The result is that this time it is the atmosphere of a house-party. Harry H[arlow] has got to London last night so missed the first two days but is now with us. (...) Tomorrow he is on the platform [and] we should probably have some firework. I confess I feel rather proud of this party, both as a convener [and] chairman, I can take much credit for the party atmosphere, [and] also because so much of the work reported owes its origin to my stimulation. We have had [three] excellent presentations (Mary Ainsworth, Peter Wolff [and] Heinz Prechtl) [and] two that were too long (Jack Gewirtz [and] Tony Ambrose). In addition, Robert [Hinde] has shone [and] Rudolf Schaffer did very well in a brief contribution. They say Thelma [Rowell] is on the best of things [and] presents her Cambridge monkeys tomorrow. (Bowlby in a letter to Ursula, September 7, 1961; AMWL: PP/BOW/B.1/24)

The study group is over [and] has been a tremendous success. Everyone has enjoyed it [and] feel they have profited from it. It has been extremely friendly [and] intense, together with cautious and effective discussion. We managed to cover a lot of ground without hurry. It is striking how far [and] fast people have developed in the two years since we last met. In a sense it has become a kind of club [and] seems likely to have far reaching effects. (Bowlby in a letter to Ursula, September 9, 1961; AMWL: PP/BOW/B.1/24)

After the last of the Ciba-symposia, Bowlby wrote to Harlow that he was “very glad indeed that you were able to be with us last week and to give us such a stimulating account of your work” (Bowlby in a letter to Harlow September 21, 1965). Bowlby’s sentiments concerning the ultimate success of the four-part series are echoed in a letter Harlow wrote to Bowlby:

It was my personal opinion that the last [Ciba-symposium] was more informative than the first two. (...) I was impressed by the fact that the people who reported both in formal papers and in discussion were far more sophisticated about the problems (...) and I think I can include myself within this generalization. Furthermore, I thought that members of the conference communicated with each other far more effectively than they had (...) and I believe that this was a result of increasing sophistication in the nature of the problems attacked and in the development of adequate measurement and techniques. I personally believe that the Tavistock series (...) achieved a great deal. (Harlow in a letter to Bowlby, October 18, 1965)

There is no doubt, then, that the Ciba-symposia achieved their goal. By bringing together major figures in the field, such as Mary Ainsworth, John Bowlby, Jack Gewirtz, Harry Harlow, Robert Hinde, Harriet Rheingold, and Theodore Schneirla, they were able to further the mutual understanding of animal psychologists, ethologist, and learning theorists, and to advance the understanding of infant behavior (Foss 1961, 1963, 1965, 1969). In particular, they allowed Bowlby and Harlow to meet on a regular basis and to discuss each other’s ideas thoroughly.

Bowlby’s Writings in the Early 1960s: Using Harlow’s Empirical Findings as a Secure Base

In the early 1960s, in several papers, Bowlby (1960a, b, 1961a, b, c) expanded upon the theme of separation anxiety. He intended it as a corollary to his earlier treatise on the child’s tie to the mother (Bowlby 1958). In a review of the literature (Bowlby 1961a; cf. Bowlby 1960a), he presented his new conceptualization of separation anxiety in the same detailed manner as he elaborated on the nature of the child’s tie to the mother in that previous paper. Before presenting his own theory, Bowlby delineated five different theories of anxiety related to the child’s attachment to the mother. First, he described ‘transformed libido’ theory, a view held by Freud until 1926, where he attributed anxiety to a child’s unsatisfied libido upon separation from an attachment figure. Second, he mentioned the view that separation anxiety may mirror birth trauma and is the counterpart to the craving of the infant in the ‘return-to-the-womb theory’ met before. The third view Bowlby discussed was that of ‘signal theory’, which held that anxiety behavior has a function and results from a safety device to ensure that the separation will not be long and implied that the child’s tie to the mother derives from a secondary drive. The fourth view presented was that of ‘depressive anxiety’, after Melanie Klein, who suggested the infant felt responsible for destroying his mother and believed he had lost her forever. Finally, Bowlby discussed ‘persecutory anxiety’, also after Melanie Klein, where the young child feels the mother has left him, because she is angry with him.

Bowlby then described his own theory as ’Primary anxiety’ theory, defining anxiety as:

a primary response not reducible to other terms and due simply to the rupture of the attachment to his mother. / The child is bound to his mother by a number of instinctual response systems, each of which is primary and which together have high survival value (...) I wish to distinguish it sharply from states of anxiety dependent on foresight. (Bowlby 1961a, pp. 253 and 267)

Bowlby (1960a) emphasized that his theory involved a new and ethologically inspired approach:

The heart of this theory is that the organism is provided with a repertoire of behaviour patterns, which are bred into it like the features of its anatomy and physiology, and which have become characteristic of its species because of their survival value to the species [original italics]. (Bowlby 1960a, p. 95)

But Bowlby now also clearly relied on the careful experiments by comparative psychologists such as Harry Harlow. In discussing fright and an animal’s escape from a fearful situation to a secure situation, he referred to the latter as a “haven of safety”, a term which he took from Harlow and Zimmermann (1958). Bowlby quoted Harlow and Zimmermann as follows:

In describing their very interesting experiments with rhesus monkeys they write: ‘One function of the real mother, human or sub-human, and presumably of a mother surrogate, is to provide a haven of safety for the infant in times of fear or danger.’ (Bowlby 1960a, p. 97)

Later in the same paper, Bowlby compared the behavior of the young child, Laura (filmed by Robertson 1952), who pretended to be asleep when a strange man entered her room, to the behavior of the rhesus infants, who froze in a crouched posture when introduced to a strange situation in the absence of the surrogate mother. That remarkable comparison too was a reference to Harlow and Zimmermann’s paper. Bowlby also discussed the infants’ rushing to the mother (if she was present) as a source of security, describing the response as so strong “it can be adequately depicted only by motion pictures” (Bowlby 1960a, p. 101). He was no doubt referring to Harlow’s film, The nature and development of affection (Harlow and Zimmermann 1959a), a film that has been shown to thousands of introductory psychology classes over the years and received an award for excellence at a European film festival in 1960.

In three other papers Bowlby (1960b, 1961b, c) of that period discussed maternal separation and the processes of grief and mourning: according to his views separation from the mother-figure would lead to separation anxiety and grief and would set in train processes of mourning. Bowlby described the three stages of protest, despair and detachment. One of the papers was based on a lecture Bowlby (1961c) read at a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Chicago in May, 1961. There Bowlby once again presented his new ideas to an audience of psychiatrists. He stressed the importance of observation instead of using retrospective evidence, described the analogous course of grief and mourning in children and adults as well as in animals, and finally pointed to the evolutionary basis of the process of mourning. To buttress his claim that “In the light of phylogeny it is likely that the instinctual bonds that tie human young to a mother figure are built on the same general pattern as in other mammalian species” (Bowlby 1961c, p. 482), Bowlby referred once again to the work of Harlow (Harlow and Zimmermann 1959b). There was no discussion of Harlow’s work beyond that, but Bowlby’s own description of the stages of protest, despair and detachment was to greatly influence Harlow’s experimenting.

Harlow’s Research in the 1960s: Seeking Empirical Evidence for Bowlby’s Theoretical Claims

Bowlby’s influence on Harlow’s work becomes evident after the first two Ciba-conferences. In two studies on mother–infant separation Harlow modeled his experiments with rhesus monkeys on the human separation syndrome described by Bowlby (Stephen Suomi, personal communication, August 27, 2006). In his experiments Harlow either physically (Seay et al. 1962) or totally (not just physically but also visually and audibly) separated (Seay and Harlow 1965) the infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers for three and two weeks respectively. In both studies, the rhesus infants initially responded with “violent and prolonged protest” and then passed into a stage of “low activity, little or no play and occasional crying”. These stages were similar to the phases of protest and despair described by Bowlby. The third phase of detachment was not found in either study, presumably because of the relatively short period of separation. Overall, Harlow reported considerable similarity in the responses to mother–infant separation in human children and infant monkeys, explicitly referring to Bowlby’s (1960b, 1961a) studies on the subject.

Bowlby’s Continuing Interest in Harlow’s Work

Ten years after their first publications on the mother–child bond (Bowlby 1958; Harlow 1958), Bowlby (1968) published a paper on the effects on behavior of the disruption of an affectional bond. In this paper he stated that “[t]here is now abundant evidence that, not only in birds but in mammals also, young become attached to mother-objects despite not being fed from that source...”, and referred to Harlow’s work with rhesus monkeys (Harlow and Harlow 1965). This statement made clear that there no longer was any empirical support for psychoanalytic and learning theorist explanations for attachment behavior.

In 1969, four years after the fourth and last Ciba-symposium, the first volume of Bowlby’s trilogy on Attachment and Loss was published. In that volume, Bowlby draws heavily on the results of Harlow’s experiments as an empirical confirmation of his ideas. Throughout this book, Bowlby makes ample use of animal evidence and biological theorizing (e.g., Lorenz, Tinbergen). Among the students of animal behavior Bowlby referred to, Harlow figured prominently. We shall mention but a few examples.

In discussing motor patterns of primate sexual behavior, Bowlby (1969/1982, p. 165) claimed there is clear evidence that they are subject to a sensitive developmental phase and pointed out Harlow’s extensive series of experiments in which rhesus infants were raised in differing social environments, “all differing greatly from the environment of evolutionary adaptedness”. Pointing out the deficits in adult heterosexual behavior displayed by the Wisconsin isolate-reared monkeys, Bowlby cited a personal communication in which Harlow wrote he was “now quite convinced that there is no adequate substitute for monkey mothers early in the socialization process” (Harlow in a letter to Bowlby dated October 18, 1965).

A chapter on the nature of attachment behavior contained a reiteration by Bowlby (1969/1982, p. 178) of the four principal theories of the child’s tie to the mother that he had disputed in his earlier paper (Bowlby 1958). This time he prefaced his own view with the interesting phrase: “Until 1958, which saw the publication of Harlow’s first papers and of an early version of the view expressed here, four principal theories regarding the nature and origin of the child’s tie were (...) found.” With that phrase, Bowlby seemed to at least implicitly make two points: first, that he and Harlow simultaneously and independently arrived at similar views, and, second, that Harlow’s findings were of fundamental importance for attachment theory and hence for his own thinking.

In a discussion of primate infant and mother roles in their joint relationship, Bowlby (1969/1982, p. 194) referred to the tenacity of primate infants brought up in human homes to cling to their foster parents and added: “Of the cases in which an infant has been brought up on an experimental dummy the best-known reports are those of Harlow and his colleagues (Harlow 1961; Harlow and Harlow 1965).” The next sub-topic (Bowlby 1969/1982, p. 195) was the infant’s ability to discriminate the mother, and Bowlby again cited Harlow and Harlow (1965) pointing out that Harlow believed a rhesus infant learned attachment to a specific mother during the first week or two of life.

In his chapter on the nature and function of attachment behavior, Bowlby connected Lorenz’s work on imprinting to Harlow’s rhesus monkey work. To support his views on the nature and function of attachment behavior, Bowlby (1969/1982, pp. 213–216) used Harlow’s experiments to undermine “the secondary drive type of theory”. He meticulously described Harlow’s (Harlow and Zimmermann 1959b; Harlow 1961) experiments with the cloth and wire mother illustrating “that ’contact comfort’ led to attachment behaviour whereas food did not” and that “typical attachment behaviour is directed to the non-feeding cloth model whereas no such behaviour is directed towards the feeding wire one”.

In developing a control systems approach to attachment behavior, Bowlby (1969/1982, p. 239) applied Harlow’s (Harlow and Harlow 1965) views on the object and social exploratory behavior of young monkeys to that of human children: just as infant monkeys, human children have an exploratory system that is “antithetic to [their] attachment behaviour”, because it takes them away from their mother.

From these few examples, it becomes clear that in the first volume of his magnum opus Attachment and Loss, Bowlby used Harlow’s empirical data on rhesus monkeys as uncontested evidence for his own views on the nature and development of the attachment relation which is formed between children and their caregivers in the first year of life. Harlow’s findings provided Bowlby with independent empirical evidence, which he could use to argue the superiority of his ideas over and above those of psychoanalysts and learning theorists.

Conclusion

In this contribution, we have taken a closer look at the cross-fertilization of the work of John Bowlby and Harry Harlow. We have demonstrated Harlow–Bowlby ties through correspondence and mutual presence at professional meetings. They wrote dozens of letters and met at least five times between 1958 and 1965. Instances in which Bowlby cited Harlow’s work in order to make a point, or as illustrative documentation of a behavior or phenomenon, have been noted. We may conclude that Harlow’s scientific influence on Bowlby has been demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt: Harlow’s experiments showed in a remarkable way what Bowlby had been theorizing about since his introduction to ethology in the early 1950s. Our findings make abundantly clear that Singer (1975) was completely wrong in asserting that Harlow’s findings had no impact on Bowlby’s theory whatsoever. A careful analysis shows that Harlow provided an important part of the solid empirical foundation for Bowlby’s theoretical construction.

In his turn, Harlow was influenced by Bowlby’s new theorizing. We have described how in two studies on separation (Seay et al. 1962; Seay and Harlow 1965) Harlow modeled his experiments on Bowlby’s ideas. Harlow’s own assertion that he and his colleagues used one of Bowlby’s paper as something of a “reference bible” (see above), his frequent requests in their correspondence for offprints of Bowlby’s papers, and his references to Bowlby’s ideas make it clear that he regarded Bowlby as one of the major theoreticians. It was Harlow’s student Suomi (1995) who acknowledged Bowlby’s major influence in three areas of animal research: (1) descriptive studies of the development of attachment and other social relationships in monkeys and apes, (2) experimental and naturalistic studies of social separation in nonhuman primates, and (3) investigations of the long-term consequences of differential early attachments in rhesus monkeys.

The scientific and personal contact between Bowlby and Harlow that started in 1957 lasted through the 1960s and early 1970s until Harlow’s retirement in 1974. They kept each other informed about their work and cited each other’s work extensively. Although they came from widely diverging backgrounds and differed in many respects they found a common denominator in their interest in the origin of affectional bonds. Together they reached the introductory psychology textbooks and influenced the lives of many children around the world.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

Berrios, G. E., & Freeman, H. L. (1991). 150 years of British psychiatry, 1841–1991. London: Gaskell.

Blum, D. (2002). Love at Goon Park. Wisconsin: Perseus.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 3, 355–534.

Bowlby, J. (1953). Critical phases in the development of social responses in man and other animals. New Biology, 14, 25–32.

Bowlby, J. (1957). An ethological approach to research in child development. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 30, 230–240.

Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 350–373.

Bowlby, J. (1960a). Separation anxiety. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 41, 89–113.

Bowlby, J. (1960b). Grief and mourning in infancy and early childhood. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 15, 9–52.

Bowlby, J. (1960c). Symposium on psycho-analysis and ethology II: ethology and the development of object relations. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 41, 313–317.

Bowlby, J. (1961a). Separation anxiety: a critical review of the literature. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1, 251–269.

Bowlby, J. (1961b). Processes of mourning. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 42, 317–340.

Bowlby, J. (1961c). The Adolf Meyer Lecture: childhood mourning and its implications for psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 118, 481–498.

Bowlby, J. (1968). Effects on behaviour of disruption of an affectional bond. In J. M. Thoday, & A. S. Parker (Eds.), Genetic and environmental influences on behaviour. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss. Vol. II: Anxiety and anger. New York: Basic.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss. Vol. I: Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic (Original work published 1969).

Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M., Boston, M., & Rosenbluth, D. (1956). The effects of mother–child separation: a follow-up study. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 29, 211–247.

Bowlby, J., Robertson, J., & Rosenbluth, D. (1952). A two-year-old goes to hospital. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 7, 82–94.

Cole, M., & Cole, S. R. (2005). The development of children (5th ed.). New York, NY: Worth.

DeHart, G. B., Sroufe, L. A., & Cooper, R. G. (2004). Child development: its nature and course (5th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Foss, B. M. (1961). Determinants of infant behaviour I. London: Methuen.

Foss, B. M. (1963). Determinants of infant behaviour II. London: Methuen.

Foss, B. M. (1965). Determinants of infant behaviour III. London: Methuen.

Foss, B. M. (1969). Determinants of infant behaviour IV. London: Methuen.

Griffiths, P. E. (2004). Instinct in the ‘50s: the British reception of Konrad Lorenz’s theory of instinctive behavior. Biology and Philosophy, 19, 609–631.

Harlow, H. F. (1943). Solution by rhesus monkeys of a problem involving the Weigl principle using the matching-from-sample method. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 36, 217–227.

Harlow, H. F. (1944). Studies in discrimination learning by monkeys: I. The learning of discrimination series and the reversal of discrimination series. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 30, 3–12.

Harlow, H. F. (1949). The formation of learning sets. Psychological review, 56, 51–65.

Harlow, H. F. (1957). Experimental analysis of behavior. American Psychologist, 12, 485–490.

Harlow, H. F. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 673–685.

Harlow, H. F. (1961). The development of affectional patterns in infant monkeys. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behaviour I (pp. 75–97). London/New York: Methuen/Wiley.

Harlow, H. F. (1963). The maternal affectional system. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behavior II (pp. 3–33). London: Methuen.

Harlow, H. F. (1977). Birth of the surrogate mother. In W. R. Klemm (Ed.), Discovery processes in modern biology (pp. 133–150). Huntington, NY: Krieger.

Harlow, H. F., & Bromer, J. A. (1938). A test-apparatus for monkeys. Psychological Record, 2, 434–436.

Harlow, H. F., & Dagnon, J. (1943). Problem solution by monkeys following bilateral removal of the prefrontal areas: I. The discrimination and discrimination-reversal problems. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 351–356.

Harlow, H. F., & Harlow, M. K. (1965). The affectional systems. In A.M. Schrier, H. F. Harlow, & F. Stollnitz (Eds.), Behavior in nonhuman primates: modern research trends (Vol. II, pp. 287–334). New York: Academic.

Harlow, H. F., & Harlow, M. K. (1969). Effects of various mother infant relationships on rhesus monkey behaviors. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of infant behavior IV (pp. 15–36). London: Methuen.

Harlow, H. F., & Settlage, P. H. (1947). Effect of extirpation of frontal areas on learning performance by monkeys. Research Publication Association for Nervous and Mental Disorders, 27, 446–459.

Harlow, H. F., & Zimmermann, R. R. (1958). The development of affectional responses in infant monkeys. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 102, 501–509.

Harlow, H. F., & Zimmermann, R. R. (1959a). Affectional responses in the infant monkey. Science, 130, 421–432.

Harlow, H. F., & Zimmermann, R. R. (1959b). The nature and development of affection [Motion picture]. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Primate Laboratory.

Hinde, R. A. (1966). Animal behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hrdy, S. B. (1999). Mother nature: A history of mothers, infants, and natural selection. New York: Pantheon.

Karen, R. (1994). Becoming attached: unfolding the mystery of the infant–mother bond and its impact on later life. New York: Warner.

Lashley, K. E. (1950). In search of the engram. Symposium of the Society of Experimental Biology, 4, 454–482.

Lehrman, D. S. (1953). A critique of Konrad Lorenz’s theory of instinctive behavior. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 28, 337–363.

Lorenz, K. Z. (1935). Der Kumpan in der Umwelt des Vogels. Journal für Ornithologie, 83, 137–213, 289–412.

Lorenz, K. Z. (1937). The companion in the bird’s world. The Auk, 54, 245–273.

Moss, E. M., & Harlow, H. F. (1948). Problem solution by monkeys following extensive unilateral decortication and prefrontal lobotomy of the contra lateral side. Journal of Psychology, 25, 223–226.

Robertson, J. (1952). A two-year-old goes to hospital [Film]. London: Tavistock Child Development Research Unit.

Robertson, J., & Bowlby, J. (1953). A two-year-old goes to hospital: a scientific film. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 46, 425–427.

Seay, B., Hansen, E., & Harlow, H. F. (1962). Mother–infant separation in monkeys. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 3, 123–132.

Seay, B., & Harlow, H. F. (1965). Maternal separation in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 140, 434–441.

Singer, P. A. D. (1975). Animal liberation: a new ethics for our treatment of animals. New York: New York Review/Random House.

Suomi, S. J. (1995). Influence of attachment theory on ethological studies of biobehavioral development in nonhuman primates. In S. Goldberg, R. Muir, & J. Kerr (Eds.), Attachment theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives (pp. 185–201). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic.

Suomi, S. J., & LeRoy, H. A. (1982). In memoriam: Harry F. Harlow (1905–1981). American Journal of Primatology, 2, 319–342.

Van der Horst, F. C. P., Van der Veer, R., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). John Bowlby and ethology: an annotated interview with Robert Hinde. Attachment & Human Development, 9(4), 321–335.

Van Dijken, K. S. (1998). John Bowlby: his early life. London: Free Association.

Van Dijken, K. S., Van der Veer, R., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Kuipers, H. J. (1998). Bowlby before Bowlby: the sources of an intellectual departure in psychoanalysis and psychology. Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences, 34, 247–269.

Van Wagenen, G. (1950). The monkeys. In E. J. Farris (Ed.), The care and breeding of laboratory animals (pp. 1–42). New York: Wiley.

Zazzo, R. (1979). Le colloque sur l’attachement. Paris: Delachaux et Niestlé.

Footnotes

1 The correspondence between Harry Harlow and John Bowlby (thus far twenty letters were recovered) resides with Helen A. LeRoy.

2 Note that reprints at the time had to be typed anew, because the Xeroxing machine was still a luxury of the future. In order to make multiple copies to exchange their writings, researchers had to resort to having papers typed several times or to reproducing them by mimeograph. On the mailing list for Harlow’s papers we find among others the names of Mary Ainsworth, Gerard Baerends, John Bowlby, Julian Huxley and René Spitz.

3 AMWL stands for Archives and Manuscripts, Wellcome Library for the History and Understanding of Medicine, 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE. The letters PP/BOW stand for Personal Papers Bowlby.

4 The four Ciba-symposia (organized in 1959, 1961, 1963 and 1965) were funded by the Ciba foundation, a foundation formed in 1949 by the Swiss company Ciba (now Novartis) that promotes scientific excellence by arranging scientific meetings. The four meetings are often also referred to as meetings of the Tavistock study group.