Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology

1963, Vol. 66, No. 4, 387-389

CRITIQUE AND NOTES

INTERACTION OF SET AND AWARENESS AS DETERMINANTS

OF RESPONSE TO VERBAL CONDITIONING

PAUL EKMAN,2 LEONARD KRASNER, AND LEONARD P. ULLMANN

Stanford University and Veterans Administration Hospital, Palo Alto, California

The utility of an operant conditioning model to psychotherapy was evaluated by studying the definition of the situation given S and S's focus on E's behavior. Instructions induced either a positive or negative set, identifying a story telling task as a test of empathy or personal problems. Awareness was induced in y^ of the Ss by calling attention to E's reinforcement "mm-hmm." 12 undergraduate students served as Ss in each of the 4 experimental groups. Positive set-Aware Ss increased use of emotional words, while Negative set- Aware Ss decreased use of emotional words. The results were interpreted as evidence that awareness can either facilitate or inhibit conditioning, depending upon S's set.

Bandura (1961), Bollard and Miller (19SO), Frank (1961), Kanfer (1961), Krasner (1961), and Marmor (1961), among others, have recognized that verbal operant conditioning offers a model situation for studying interpersonal variables relevant to psychotherapy. The present paper reports on the interaction of two variables which are central to a determination of the utility of this model: the definition of the situation given the subject (set) and the subject's focus on the experimenter's behavior (awareness). The experimental procedure within which these variables were studied was made to resemble psychotherapy in four ways: First, emitted (free operant) verbal behavior was conditioned rather than elicited (sentence completion) verbal behavior (Taffel, 19SS). Second, the "sets" experimentally created were relevant to psychotherapy: "personal problems" versus "empathy" or health. Next, the situation was a TAT-like one, and finally, the reinforced verbal class was one which had been developed and documented in a clinical setting.

METHOD

Set and awareness were manipulated by alterations in the instructions given to the subjects prior to the conditioning task. A positive set was induced by telling the subject that the procedure was a test of empathy, or warmth and feeling towards people. A negative set was induced by characterizing the task as a test of personal problems and difficulties in 1 This research was supported, in part, by Research Grant M-2458, from the National Institute of Mental Health, United States Public Health Service. 8 Now at the University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco.

getting along with people. Awareness was induced in half the subjects by telling them that the experimenter would indicate that they were either revealing personal problems or showing empathy by going "mm-hmm." There were four experimental groups all of whom were given the following instructions: This is a new personality test that we are trying out. I have here a. set of cards with drawings of people. I want you to make up an imaginative story about each card. In telling your story mention something about the present: what is going on now; the past; what led up to or otherwise explains the present; and the future: the outcome of the story. In other words, a complete imaginative story. Feel free to tell any kind of story you wish. Make it interesting to yourself. The only restriction on your stories is the time. Each story must last for a full 4 minutes. [Demonstrate clock] Frequently you will still be talking when the clock goes off. When that happens, just stop and I'll give you another card. To save my having to write, we'll tape record it.

In addition to the above instructions each of the subgroups was given instructions as follows: [Positive set-Nonaware] We are hoping that in telling these stories you will show how much empathy you have for others. Your stories will be scored for the amount of warmth and feeling you have towards other people.

[Positive set-Aware] We are hoping that in telling these stories you will show how much empathy you have for others. Your stories will be scored for the amount of warmth and feeling you have towards other people. After your first few stories I will let you know that you are showing warmth by going "mm-hmm" whenever you do this.

TABLE 1

EFFECT OF SET AND EXPERIMENTALLY MANIPULATED

"AWARENESS" ON INCREASED USE OF EMOTIONAL

WORDS DURING REINFORCED TRIALS

[Negative set-Nonaware] we are hoping that in telling these stories you will show your own per- sonal problems and difficulties in getting along with others. Your stories will be scored for the amount of personal problems you have in dealing with other people.

[Negative set-Aware] We are hoping that in telling these stories you will show your own personal problems and difficulties in getting along with others. Your stories will be scored for the amount of personal problems you have in dealing with ' other people. After your first few stories I will let you know that you are revealing your own personal problems by going "mm-hmm" whenever you do this.

Task. Subjects were presented cards with simple line drawings of people engaged in commonplace activities, such as buying ties, fishing, or getting a haircut (Weiss, Krasner, & Ullmann, 1960). The TATlike instructions were to tell imaginative 4-minute stories. Each 4-minute story defined a trial and all stories were tape recorded for later scoring. There were four trials. The first and second trials were used to obtain "operant level" and were not reinforced. During the third and fourth trials, emotional words (EW), as defined by Ullmann and McFarland (1957), were reinforced by the experimenter who nodded his head and said "mm-hmm" as if in agreement each time the subject used an emotional word.

Subjects. Forty-eight undergraduate males and females served as subjects. The proportion of males and females was balanced across the four groups. Procedure. Subjects were seen individually in the same experimental room. The variable of social deprivation-social enhancement (Gewirtz & Baer, 1958; Kanfer & Karas, 1959; Walters & Karal, 1960) Was attenuated by all subjects first completing a picture identification task (Ekman, 1961). Subjects were then introduced to the conditioning task by the above instructions. Subjects were assigned to experimental groups in terms of order of their appearance. All stories were tape recorded, and a clock was used to time each story.

RESULTS

Scoring reliability by three raters of single nonreinforced trials of college undergraduate protocols had in previous research (Weiss et al., 1960) yielded a coefficient of concordance at the .001 level. Since two trials were used for establishing both operant and reinforced levels, reliability was at least, and probably greater than, .90.

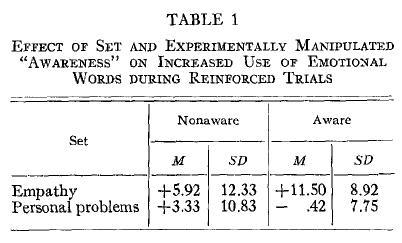

The four experimental groups did not differ from each other on number of EW used during operant trials (all the F ratios were less than unity). Because there were no systematic differences during operant trials, a 2 X 2 analysis of variance was completed on the differences between number of EW used during operant and reinforced trials. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the four groups. The F ratio for rows (Empathy-Personal problems) was significant past the .05 level (F = 5.66, df=l/44), while the F ratio for columns (Aware-Nonaware) was insignificant (F = .09) and the interaction approached, but did not reach, statistical significance (^ = 2.34). The most important difference was between groups of "aware" subjects: aware subjects who had been told that the situation was a measure of empathy increased an average ctf 11.5 EWs while aware subjects who had been told that the situation was a measure of personal problems on the average decreased .5 an EW. The difference between these two groups was significant beyond the .01 level (# = 3.56).

DISCUSSION

Although many of the early studies in verbal conditioning reported evidence for "learning without awareness" (Adams, 1957; Krasner, 1958), later studies have focused on a number of methodological issues which have brought into doubt the interpretations of these early findings (Dulany, 1961; Eriksen, 1960; Levin, 1961; Matarazzo, Saslow, & Pareis, 1960; Spielberger, 1961; Spielberger, Levin, & Shepard, 1962). A previous study (Krasner, Weiss, & Ullmann, 1961) has demonstrated that "awareness" can be manipulated by instructional set in such a way as to differentially affect responsivity. The problem has also been approached by varying the amount of information given to the subject (Tatz, 1960), varying the "task relevant information" (Kanfer & Marston, 1961, 1962), and using instructional set to create "high threat" and "low threat" experimental situations (Sarason & Ganzer, 1962). The manipulation of "awareness" by various instructional sets avoids the pitfalls of ascertaining "awareness" in an interview after the completion of the conditioning task. The present results show that set and awareness cannot be considered separately, but that induced awareness will differentially affect conditioning depending upon the subject's orientation towards the task. Thus heightening the subject's attention or alertness to the reinforcement contingency does not in itself predict whether conditioning will be facilitated or inhibited. If the subject believes that there is something unpleasant or undesirable about the response being reinforced, then increased awareness will lead him to inhibit or suppress his use of the response class the experimenter is "reinforcing." On the other hand, increased awareness may facilitate behavior change if the subject's set has been positive, leading him to view the experimenter's "reinforcing" behavior as an indication of favor.

REFERENCES

ADAMS, J. Laboratory studies of behavior without awareness. Psychol. Bull, 19S7, 54, 383-405. BANDURA, A. Psychotherapy as a learning process. Psychol. Bull, 1961, 58, 143-159.

DOIXARD, J., & MILLER, N. E. Personality and psychotherapy. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1950.

DULANY, D. E., JR. Hypotheses and habits in verbal "operant conditioning." J. abnorm. soc. Psychol, 1961, 63, 251-263.

EKMAN, P. Body language during interviews. Paper read at Inter-American Congress of Psychology, Mexico City, December 1961.

ERIKSEN, C. W. Discrimination and learning without awareness: A methodological survey and evaluation. Psychol. Rev., 1960, 67, 279-300.

FRANK, J. D. Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univer. Press, 1961.

GEWIRTZ, J. JL, & BAER, D. M. Deprivation and satiation of social reinforcers as drive conditions. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1958, 57, 165-172. KANFER, F. H. Comments on learning in psychotherapy. Psychol. Rep., 1961, 9, 681-699.

KANFER, F. H., & KARAS, SHIRLEY C. Prior experimenter- subject interaction and verbal conditioning. Psychol. Rep., 1959, 5, 345-353.

KANFER, F. H., & MARSTON, A. R. Verbal conditioning, ambiguity, and psychotherapy. Psychol. Rep., 1961, 9, 461-475.

KANFER, F. H., & MARSTON, A. R. The effect of taskrelevant information on verbal conditioning. J. Psychol., 1962, 53, 29-36.

KRASNER, L. Studies of the conditioning of verbal behavior. Psychol. Bull., 1958, 55, 148-170.

KRASNER, L. The therapist as a social reinforcement machine. Paper read at Second Conference on Research in Psychotherapy, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, May 1961.

KRASNER, L., WEISS, R. L., & ULLMANN, L, P. Responsivity to verbal conditioning as a function of awareness. Psychol. Rep., 1961, 8, 523-538.

LEVIN, S. M. The effects of awareness on verbal conditioning. /. exp. Psychol., 1961, 61, 67-75.

MARMOR, J. Psychoanalytic therapy as an educational process: Common denominators in the therapeutic approaches of different psychoanalytic "schools." Paper read at Academy of Psychoanalysis, Chicago, May 1961.

MATARAZZO, J. D., SASLOW, G., & PAREIS, E. N. Verbal conditioning of two response classes: Some methodological considerations. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1960, 61, 190-206.

SARASON, I. G., & GANZER, V. J. Anxiety, reinforcement, and experimental instructions in a free verbalization situation. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1962, 65, 300-307.

SPIELBERGER, C. D. The role of awareness in verbal conditioning. Paper read at American Psychological Association, New York, September 1961.

SPIELBERGER, C. D., LEVIN, S. M., & SHEPARD, MARY C. The effects of awareness and motivation towards the reinforcement on operant conditioning of verbal behavior. J. Pers., 1962, 30, 106-121.

TAFFEL, C. Anxiety and the conditioning of verbal behavior. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol, 1955, 51, 496- 501.

TATZ, S. J. Symbolic activity in "learning without awareness." Amer. J. Psychol, 1960, 73, 239-247. ULLMANN, L. P., & MCFARLAND, R. L. Productivity as a variable in TAT protocols: A methodological study. /. pro). Tech., 1957, 21, 80-87.

WALTERS, R. H., & KARAL, PEARL. Social deprivation and verbal behavior. J. Pers., 1960, 28, 89-107.

WEISS, R. L., KRASNER, L., & ULLMANN, L. P. Responsivity to verbal conditioning as a function of emotional atmosphere and pattern of reinforcement. Psychol Rep., 1960, 6, 415-426. (Received January 27, 1962)

www.psychspace.com心理学空间网