Forming Impressions of Personality

Solomon Asch 2017-8-01

We look at a person and immediately a certain impression of his character forms itself in us. A glance, a few spoken words are sufficient to tell us a story about a highly complex matter. We know that such impressions form with remarkable rapidity and with great ease. Subsequent observation may enrich or upset our first view, but we can no more prevent its rapid growth than we can avoid perceiving a given visual object or hearing a melody. We also know that this process, though often imperfect, is also at times extraordinarily sensitive.

This remarkable capacity we possess to understand something of the character of another person, to form a conception of him as a human being, as a center of life and striving, with particular characteristics forming a distinct individuality, is a precondition of social life. In what manner are these impressions established? Are there lawful principles regulating their formation?

One particular problem commands our attention. Each person confronts us with a large number of diverse characteristics. This man is courageous, intelligent, with a ready sense of humor, quick in his movements, but he is also serious, energetic, patient under stress, not to mention his politeness and punctuality. These characteristics and many others enter into the formation of our view. Yet our impression is from the start unified; it is the impression of one person. We ask: How do the several characteristics function together to produce an impression of one person? What principles regulate this process?

We have mentioned earlier that the impression of a person grows quickly and easily. Yet our minds falter when we face the far simpler task of mastering a series of disconnected numbers or words. We have apparently no need to commit to memory by repeated drill the various characteristics we observe in a person, nor do some of his traits exert an observable retroactive inhibition upon our grasp of the others. Indeed, they seem to support each other. And it is quite hard to forget our view of a person once it has formed. Similarly, we do not easily confuse the half of one person with the half of another. It should be of interest to the psychologist that the far more complex task of grasping the nature of a person is so much less difficult.

There are a number of theoretical possibilities for describing the process of forming an impression, of which the major ones are the following:

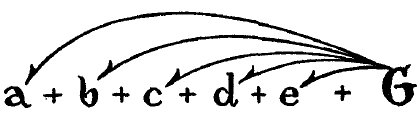

1. A trait is realized in its particular quality. The next trait is similarly realized, etc. Each trait produces its particular impression. The total impression of the person is the sum of the several independent impressions. If a person possesses traits a, b, c, d, e, then the impression of him may be expressed as:

I. Impression = a + b + c + d + e

Few if any psychologists would at the present time apply this formulation strictly. It would, however, be an error to deny its importance for the present problem. That it controls in considerable degree many of the procedures for arriving at a scientific, objective view of a person (e.g., by means of questionnaires, rating scales) is evident. But more pertinent to our present discussion is the modified form in which Proposition I is applied to the actual forming of an impression. Some psychologists assume, in addition to the factors of Proposition I, the operation of a "general impression." The latter is conceived as an affective force possessing a plus or minus direction which shifts the evaluation of the several traits in its direction. We may represent this process as follows:

Ia. Impression =

To the sum of the traits there is now added another factor, the general impression.

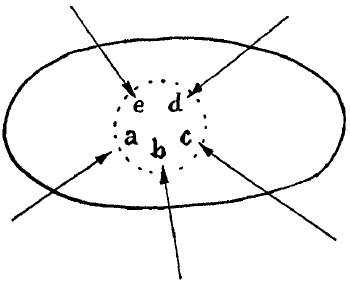

2. The second view asserts that we form an impression of the entire person. We see a person as consisting not of these and those independent traits (or of the sum of mutually modified traits), but we try to get at the root of the personality. This would involve that the traits are perceived in relation to each other, in their proper place within the given personality. We may express the final impression as

II. Impression =

It may appear that psychologists generally hold to some form of the latter formulation. The frequent reference to the unity of the person, or to his "integration," implying that these qualities are also present in the impression, point in this direction. The generality of these expressions is, however, not suitable to exact treatment. Terms such as unity of the person, while pointing to a problem, do not solve it. If we wish to become clear about the unity in persons, or in the impression of persons, we must ask in what sense there is such unity, and in what manner we come to observe it. Secondly, these terms are often applied interchangeably to Propositions II and Ia. It is therefore important to state at this point a distinction between them.

For Proposition II, the general impression is not a factor added to the particular traits, but rather the perception of a particular form of relation between the traits, a conception which is wholly missing in Ia. Further, Proposition Ia conceives the process in terms of an imposed affective shift in the evaluation of separate traits, whereas Proposition II deals in the first instance with processes between the traits each of which has a cognitive content. Perhaps the central difference between the two propositions becomes clearest when the accuracy of the impression becomes an issue. It is implicit in Proposition II that the process it describes is for the subject a necessary one if he is to focus on a person with maximum clarity. On the other hand, Proposition Ia permits a radically different interpretation. It has been asserted that the general impression "colors" the particular characteristics, the effect being to blur the clarity with which the latter are perceived. In consequence the conclusion is drawn that the general impression is a source of error which should be supplanted by the attitude of judging each trait in isolation, as described in Proposition I. This is the doctrine of the "halo effect" (9).

With the latter remarks, which we introduced only for purposes of illustration, we have passed beyond the scope of the present report. It must be made clear that we shall here deal with certain processes involved in the forming of an impression, a problem logically distinct from the actual relation of traits' within a person. To be sure, the manner in which an impression is formed contains, as we shall see, definite assumptions concerning the structure of personal traits. The validity of such assumptions must, however, be established in independent investigation.

The issues we shall consider have been largely neglected in investigation. Perhaps the main reason has been a one-sided stress on the subjectivity of personal judgments. The preoccupation with emotional factors and distortions of judgment has had two main consequences for the course investigation has taken. First, it has induced a certain lack of perspective which has diverted interest from the study of those processes which do not involve subjective distortions as the most decisive factor. Secondly, there has been a tendency to neglect the fact that emotions too have a cognitive side, that something must be perceived and discriminated in order that it may be loved or hated. On the other hand, the approach of the more careful studies in this region has centered mainly on questions of validity in the final product of judgment. Neither of the main approaches has dealt explicitly with the process of forming an impression. Yet no argument should be needed to support the statement that our view of a person necessarily involves a certain orientation to, and ordering of, objectively given, observable characteristics. It is this aspect of the problem that we propose to study.

Forming a Unified Impression: Procedure

The plan followed in the experiments to be reported was to read to the subject a number of discrete characteristics, said to belong to a person, with the instruction to describe the impression he formed. The subjects were all college students, most of whom were women. They were mostly beginners in psychology. Though they expressed genuine interest in the tasks, the subjects were not aware of the nature of the problem until it was explained to them. We illustrate our procedure with one concrete instance. The following list of terms was read:

energetic — assured — talkative — cold — ironical — inquisitive — persuasive.

The reading of the list was preceded by the following instructions:

I shall read to you a number of characteristics that belong to a particular person.

Please listen to them carefully and try to form an impression of the kind of person described. You will later be asked to give a brief characterization of the person in just a few sentences. I will read the list slowly and will repeat it once.

The list was read with an interval of approximately five seconds between the terms. When the first reading was completed, the experimenter said, "I will now read the list again," and proceeded to do so. We reproduce below a few typical sketches written by subjects after they heard read the list of terms:

He seems to be the kind of person who would make a great impression upon others at a first meeting. However as time went by, his acquaintances would easily come to see through the mask. Underneath would be revealed his arrogance and selfishness.

He is the type of person you meet all too often: sure of himself, talks too much, always trying to bring you around to his way of thinking, and with not much feeling for the other fellow.

He impresses people as being more capable than he really is. He is popular and never ill at ease. Easily becomes the center of attraction at any gathering. He is likely to be a jack-of-all-trades. Although his interests are varied, he is not necessarily well-versed in any of them. He possesses a sense of humor. His presence stimulates enthusiasm and very often he does arrive at a position of importance.

Possibly he does not have any deep feeling. He would tend to be an opportunist. Likely to succeed in things he intends to do. He has perhaps married a wife who would help him in his purpose. He tends to be skeptical.

The following preliminary points are to be noted: 1. When a task of this kind is given, a normal adult is capable of responding to the instruction by forming a unified impression. Though he hears a sequence of discrete terms, his resulting impression is not discrete. In some manner he shapes the separate qualities into a single, consistent view. All subjects in the following experiments, of whom there were over 1,000, fulfilled the task in the manner described. No one proceeded by reproducing the given list of terms, as one would in a rote memory experiment; nor did any of the subjects reply merely with synonyms of the given terms.

2. The characteristics seem to reach out beyond the merely given terms of the description. Starting from the bare terms, the final account is completed and rounded. Reference is made to characters and situations which are apparently not directly mentioned in the list, but which are inferred from it.

3. The accounts of the subjects diverge from each other in important respects. This will not be surprising in view of the variable content of the terms employed, which permits a considerable freedom in interpretation and weighting.

In the experiments to be reported the subjects were given a group of traits on the basis of which they formed an impression. In view of the fact that we possess no principles in this region to help in their systematic construction, it was necessary to invent groupings of traits. In this we were guided by an informal sense of what traits were consistent with each other.

The procedure here employed is clearly different from the everyday situation in which we follow the concrete actions of an actual person. We have chosen to work with weak, incipient impressions, based on abbreviated descriptions of personal qualities. Nevertheless, this procedure has some merit for purposes of investigation, especially in observing the change of impressions, and is, we hope to show, relevant to more natural judgment.

More detailed features of the procedure will be described subsequently in connection with the actual experiments. We shall now inquire into some of the factors that determine the content and alteration of such impressions.